An important step in any IT risk management process is to clearly define the information assets in scope. But what is an information asset really? How can you best describe your important information assets? And why is it so important to spend time on establishing a suitably detailed asset overview before commencing your risk assessment?

In this article, we discuss the steps involved in identifying and describing your information assets. It is important to understand your organization’s critical information assets, as it is the threats towards these assets and the potential losses from such a threat materializing that should guide the level of information security surrounding that particular asset. In other words, information assets are one of the core components of a good risk scenario, and failure to identify all relevant assets causes inaccuracies to add up and make your risk assessment less reliable.

What is an information asset?

As with risk, information assets are not a clearly defined concept. To avoid a greater semantic discussion, we will assume that an asset is “An item of value owned”. In this context, information assets are then an information-related item (tangible or otherwise) that has value to your organization (we use assets and information assets interchangeably in the rest of this article). This definition is a start, but it is too wide. It encompasses everything from sensitive customer information to virtual servers and supplier relations. So we categorize the assets: First, we narrow our scope down to relevant (important or LtO) assets. Then we categorize our assets into primary and secondary assets.

In the classic structure of a risk assessment (risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation), identification of information assets is a substantial part of the risk identification phase. Most, if not all, national and international regulations and frameworks on information risk include some form of asset identification in their requirements.

We provide you with five steps you can take to identify your most important information assets and show you how to apply them in the wider risk assessment process. The five steps are:

- Establish context and scope. What is the width and depth of your risk assessment?

- Establish criteria for considering an asset important to your organisation.

- Identify information assets and evaluate importance.

- Validate your assets against the organisation. Have you overlooked any?

- Anchor and revisit your overview ongoingly as part of the risk management process.

Relevant information assets

Deciding which assets are relevant to your particular risk assessment will depend on steps 1 and 2 below. However, you will always need to limit the assets in scope in some way to avoid drowning in the process. In this article, we describe these assets as relevant information assets.

At the executive level, these may be highly generalized definitions that pass as License to Operate assets. This could be client transactional data and transaction flow for your webshop business or highly confidential documents about the strategic direction, like an upcoming merger.

At a local team-level, the assets may be defined in more detail, as there are fewer of them. We will discuss this further in step 2. In the IT support team, assets may be interpreted as individual PCs, servers, etc.

Primary and secondary assets

Regardless of your scope, it is often useful to distinguish between primary and secondary information assets.

Primary information assets are the information (data) that the organization gather, store, process and generate. It may also be expanded to include specific value streams (if your organization sell processes rather than products). Examples of primary assets are client transactional data, client account data, employee data, internal confidential information, source code, or accounting data.

Secondary assets are information assets that support or enable the primary assets. They are not less important, but their main purpose is to enable the correct, timely and secure delivery of primary assets. Secondary assets also tend to be the assets associated with specific vulnerabilities.

Secondary assets can be systems – Your email system, CRM platform, ERP system etc. But secondary assets may also be:

- Physical locations (main offices, meeting facilities),

- key employees with unique knowledge or insight,

- supplier relations necessary to deliver primary assets, or

- any other item (material or otherwise) necessary to deliver primary assets.

In short, an information asset is not just “one specific thing”; rather, it is a tool for communicating how certain categories or groups of information or processes together have value to the organization.

Step 1: Establish context and scope

Establishing the context of your risk assessment is an often overlooked step. This is unfortunate, as incorrectly interpreting the context of your risk assessment can lead to you processing too many or the wrong risks. This makes your risk assessment less useful in the ongoing work to reduce risks for your organization, partly because the law of diminishing returns applies to information risk. More detail does not necessarily equal more security and less risk. This is especially true if you fail to maintain the detailed view over time.

One of the most difficult aspects of defining information assets is to find a balanced level of abstraction. You want to generate a list of information assets that are detailed enough to describe the most important internal dependencies and value-carrying assets but also short enough that the company can maintain the register over time in a structured way.

You may want to start identifying relevant assets right away, but if you haven’t first considered what context your risk management activities exist in, the likelihood that you either overlook substantial risk areas or need to start over several times is high.

Establishing context tends to happen before the actual risk assessment is initiated (see, e.g. ISO-27005). You need to investigate this context and obtain agreement with relevant stakeholders in your organization before you begin identifying risk scenarios and the assets affected.

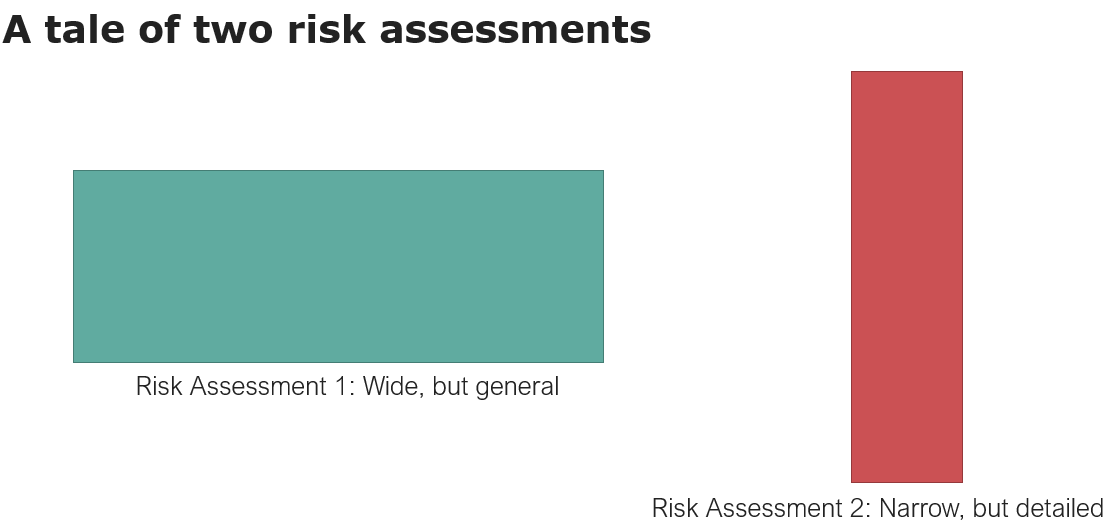

How you define your assets – where you slice the cake – can be boiled down to two dimensions: The width and depth of your asset register. You likely do not have the resources to establish a full-width, in-depth risk assessment. Your task is to find an optimal balance between the two dimensions. And you’re not limited to just one risk assessment. For instance, one wide and shallow risk assessment, along with a few very narrow but detailed risk assessments, will have a smaller overall area (required work) than one risk assessment that is both wide and deep.

Width (scope)

What is the scope of your risk assessment these assets are needed for? Does it include the entire IT organization or just a single system? What risks are already being handled elsewhere in your organization or existing processes? E.g. operational risk, financial risk, project risk etc.

These may overlap, so make it clear in writing where you expect to see overlap and what risk areas you choose to include or exclude based on your observations. Are some risks so frequent or consequences so small that they should be treated as part of an operations budget rather than a risk?

Depth (level of detail)

When you understand your scope – the width of your risk assessment, you should define the depth of the risk assessment. Does it provide value for your executive management to know exactly what application in your supplier’s microservice architecture is vulnerable to a very specific 0-day vulnerability? Would you be able to maintain such an overview?

The depth tends to be controlled by your business model in the area of IT and your resources and time allocated to conduct the risk assessment.

If you do not have competencies internally that understand the technical details of your setup, don’t attempt to maintain a technical, detailed register of server names and other components at your suppliers. Instead, start by describing systems or processes in more general terms (the sales process, the invoicing system, the website). Remember the supporting business processes (the infrastructure that enables it all). With this level of overview, you can choose to dive into more detail with selected areas. Just remember that more details do not necessarily mean a more accurate risk assessment. The law of diminishing returns applies here as well.

Step 2: Establish inclusion criteria

The goal of this step is to formalize the criteria for including an asset in your asset register. As noted earlier, these requirements for what makes an asset relevant to your particular risk assessment will vary. However, in this chapter, we will dive into a few of the more common inclusion criteria.

License to Operate (LtO) assets

A License to Operate asset is the “important and/or most protection-worthy assets and activities that support an organization’s operations and income.” As defined in the Board Leadership Society’s guide on cyber security for the Board of Directors (v. 4). The notion of a License to Operate asset favors a wide but shallow scope.

Important or critical assets

The notion of “important or critical” here is derived from the executive order on outsourcing for financial institutions. With little effort, it can be applied to assess assets in general and not only outsourcing arrangements. Similar notions of important or critical assets are being discussed or implemented already for other IT-related legislation.

From these two notions of what makes an asset important/critical/LtO, you can build a series of questions as below to help you categorize the assets you identify as relevant or not. Remember to document the steps. See the example below:

An information asset (primary or secondary) can be considered critical/important/LtO for our organization if compromise of confidentiality (e.g. data leak), integrity (correctness of data) or availability (e.g. breakdowns or cyber-attacks) can result in:

- A significant reduction in our financial results (e.g. consequences for reputation, short- or long-term economic robustness and viability or operational stand-still).

- A significant reduction in our ability to conduct our activities in a sound and justifiable way (e.g. our ability to monitor and manage risk, conduct audits and ensure business continuity).

- A significant reduction in our ability to operate in compliance with relevant regulatory requirements (e.g. are our services subject to licensing or approval? Is the service a primary source of data for mandatory regulatory reporting)?

At this early point, it may be too early to add numbers to the abovementioned requirements. You can always remove or modify assets or definitions at a later point if your interpretation of “significant reduction” turns out to vary too much.

At the end of this step, you should have written a protocol for classifying an identified asset as relevant to your risk assessment. Requirements will vary, but you can use the example above for reference.

Step 3: Identify information assets and evaluate criticality

During this step, you will gather and categorize information assets. You can do this in several ways, but I recommend taking a top-down approach as follows:

- You have already clarified the context and scope of your risk assessment in steps 1 and 2. You also have a list of inclusion criteria that you can evaluate assets against.

- Start by identifying primary assets in scope. Ask: If you could only have one primary asset, how would you describe it? Take this Frankenstein-primary asset (“All our customer data and employee data and all internal data labelled confidential”) and break it into meaningful chunks. Repeat this process until you are satisfied with the level of detail. For a general risk assessment in a smaller organization, a suitable number of primary assets could initially be 3-10. For each asset, check it against the requirements from step 2. Obtain information from relevant senior management and executives.

- Identify the secondary assets that play a significant role in delivering the identified primary assets. Talk to product owners and managers in your organization first and focus on the big picture. Add details, if necessary, by talking to technical experts. Any secondary asset may support one or more primary assets. For each asset, check it against the requirements from step 2.

You may reach step 3 and decide to go back and update your primary assets. Repeat these two steps until you find the primary and secondary assets to be somewhat stable. You have an initial list of primary assets and secondary assets.

Note: It is also possible to conduct a bottom-up identification process. This can be done by starting with a brainstorm, and discussing which systems or system groups you may have in your organization. Start with existing lists, such as a list of IT suppliers, an organizational diagram, or an assets list from the IT service management team. The goal is to gather a gross-list and group these assets until you have a manageable overview. The bottom-up approach is a good complement to the top-down approach but can become extremely labor-intensive if you are not careful. I would advise only using it as a validation step (see step 4) or supporting approach to the top-down described above.

Step 4: Validate your assets against the organization

You now have a register with your primary and secondary information assets. If you have a list of more than 10 primary assets, consider that you may still want to group them into even more general categories. Regardless of how you have established your overview, you now need to validate it. The most effective way to validate your assets is to share relevant parts of the asset list – primary and secondary assets – with the individual departments in your organization. Look at your organizational diagram and reach out to each department. Each department must be able to confirm that:

- Yes, we recognize the assets in your list. If not, renaming or a more detailed description may be needed.

- Yes, we agree that each of these assets is relevant within the scope (compared to the criteria defined in step 2). If not, you may wish to mark them not-in-scope.

- Considering the tools and information, we use on a daily, monthly, or yearly basis; we do not recognize that anything relevant is missing from this overview (if in doubt, add a note).

There are other steps you can take, too. The bottom-up-approach described under step 3 is a good way to validate your secondary assets. Consider the existing overviews of supplier arrangements (talk to legal or finance), servers, systems, etc., in your organization. Can you get them all to “fit” into your boxes?

Be aware of the areas that are frequently missed: Is the HR department using cloud solutions outside of your primary providers? Is the secretariat using a special system to communicate with board of directors? Who provides networking infrastructure for your physical locations or phones (mobile and IP phones)?

Cloud solutions. If you use one IT provider to deliver a large part of your IT portfolio, you must be aware of their use of cloud providers. From an IT-risk perspective, it does not matter if your direct provider has great information security if the cloud provider (Salesforce, Microsoft 365 etc.) experiences a major outage. These secondary assets are often relevant to discuss, even though they act as subcontractors.

Step 5: Anchor, revisit, repeat.

Only register what you can maintain. Do it. Document it.

These are the two mantras I recommend you remember for this step of the process. An asset-register, that is updated only once is not very useful. The best register is one where you can maintain some degree of automated or semi-automated overview whenever new systems are commissioned, new business areas are investigated, and so on. Yes, you may want to register a lot of different metrics that *can* tell you something about the exposure of these different assets. But consider that you must be able to maintain the register to a reasonable degree in your daily work. Less is often more useful.

Do what you document, and document what you do. This principle is simple but frequently forgotten – especially the second part. If you operate in a field where you may be subject to internal, external or regulatory audits, be sure to document your decisions along the way. If you choose not to include a system or an asset, document it. It will make it much easier for you or a colleague to update the register in the future if they can refer back to the reasoning why a particular asset was included or not.

Finally, don’t expect to have the perfect overview, to begin with. Start small, establish 3-10 primary assets, and extract the secondary assets from there. From then on, steps 3 and 4 can be repeated to incrementally develop the overview. It is often easier for others to recognize what is wrong than to recognize what is missing.

Step 4 is a useful starting point when you need to revisit or review your risk assessment. Unless major organizational changes occur, you can get away with asking departments to validate the current overview and spot-checking using one or two of the other methods mentioned.

Finally, make sure the responsibility for maintaining the asset register is anchored. Preferably with a specific role or person and integrated into existing processes such as the risk assessment process (naturally), the IT-supplier procurement process or the IT-project management process.